Original Post: 25 Mar 2014

By Julia Ström

Picture models: Julia Yli-Hukka and Julia Ström

The information and views in this post are those of the author.

We are all used to pain; getting hit in the face, in the head, on the hands… The list could go on forever. For most of us its no big deal, some of you have suffered breaks or snapped tendons. Bruises and peeled skin are common. For some it’s even a trigger to make you go faster, harder and more fiercely. I for one get pumped after a good whack, I feel the adrenaline soaring and my attention rocketing.

However there are certain kinds of pain that shouldn’t be ignored or glorified. These are the ones that tell you to slow down, to allow your body to rest and recover. In today’s society, not just within the HEMA community, this is becoming less and less “acceptable” with slogans like “shut up and train”, “endure the pain, enjoy the gain” and “if it’s not hurting, it’s not working”. Fair enough, a certain amount of pain from exercise is to be expected, especially in high-contact, high speed sports like HEMA. Also, fun fact: women have, on average, a higher pain threshold, and according to many studies, a higher endurance level for pain.

When you feel continuous ongoing pain, which can be a stabbing, a dull or a coming-and-going intermittent pain, its time to pay attention to your body. In this article I will reflect upon some common points of injury. I’m not claiming these are exclusive to women, far from it, but this is an attempt to reflect on the injuries brought up in discussion in the Esfinges forum, and things I feel are important.

As many of you expressed, fencing does tend to exacerbate pre-existing injuries, which goes for most high intensity sports. I would however like to point out that there are some physical differences when it comes to biomechanics that make women more susceptible to certain types of injuries.

These include:

● Lower percentage of lean body mass, i.e. less muscle per kilogram of bodyweight.

● Larger range of motion in joints.

● No compensation of increased range of motion in the form of stronger/more extensive ligaments.

Women’s muscles are not weaker per kg of muscle. There is no statistical difference in strength per cross section area of muscle in male and female athletes, but the fact that we on average have smaller and leaner muscles means that we exert less power (1). But if viewed as strength exertion in relation to cross section area of muscle, there is no statistical difference!

If we take a look at the real life situation we see that this means women have approximately 40-60% less upper body strength and 25-20% less lower body strength than men. This difference persists even when we correct for body mass, although it is then reduced to a 5-15% weakness, women compared to men (1).

The results of these differences are visible in other sports, most notably for example within soccer where the amount of knee injuries is significantly higher for women compared to men, to the point where the female gender is considered to be a risk factor for anterior cruciate ligament injuries (2).

The upper extremity is up first as it is an excellent example of ligaments and muscles working together to stabilize some very unstable joints that are put through a lot of stress, particularly in sports like HEMA. The only bony connection between the arm and the thorax is the collarbone, anchoring it to the front of your ribcage. All other attachments, including the shoulder blade, are only held in place by ligaments and muscles. They are part of a chain that starts at your sternum and ends to your fingertips. As has been pointed out, we tend to have larger “forward” than “backward” muscles in the upper extremity and thorax. This is due to the fact that we exert a lot of force delivering our blows, but the strain is considerably less when it comes to retracting after having delivered a blow. This in itself builds up a certain imbalance in muscle development, an unevenness in our bodies that increases the tendency to develop strain related pain and injuries.

The shoulder has an extremely shallow socket, and depending on the plane of motion you can move your arm up to 180°, as seen from the shoulder. I won’t go into details, but much of the force of our arm is facilitated by surrounding muscles in the region of the shoulder, neck and upper back.

Something that is of particular interest is the so called “rotator cuff”, which is a set of four muscles that along with ligaments of the shoulder joint serve as the primary stabilizer of that joint itself (3). These four muscles are all relatively small, and can be strained or suffer inflammation as a result of repetitive stress (4). This is where swords come in. Swordfighting involves repetitive motion with high speed and high force, even for those of you using lighter weapon types. Not unsurprisingly your rotator cuff is at risk, and when the rotator cuff suffers injury or strain it starts to “fail”, the body starts incorporating other muscle groups that are primarily used to exert force, in order to stabilize the joint and your motion. This results in tension which can be a large component of shoulder, back and neck pain.

Inflammation requires a decreased intensity of training, and use of analgesics for a limited amount of time is usually a good idea. In order to prevent recurrence, however, it is a good idea to train the muscles in your rotator cuff, and surrounding areas. It is partly to increase strength, but also to give yourself a buffer to handle higher levels of stress.

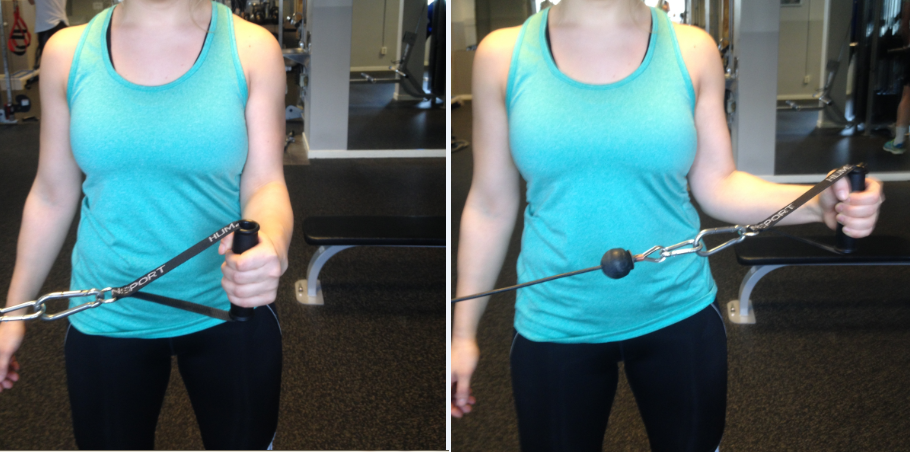

Muscular resistance training exercise to train the rotator cuff, movement outward from body

Muscular resistance training exercise to train the rotator cuff, movement toward body

As for the elbow joint, it consists of three different joints that work together in flexion and rotation (5). There are two shallow sockets of the ulna and the radius in the lower arm, working with the large joint head of the humerus in the upper arm and with each other. This complex elbow joint is more stable than that of the shoulder, however over-extension and over-rotation are problematic here, as these motions are primarily controlled by the tensile strength of ligaments, and to a certain degree a bony prominence known as the olecranon (aka the point of your elbow). In addition to this, it is one of the joints that women on average have a larger range of motion in compared to men. Large forces working across the elbow can weaken the ligament, which means that your body has to rely more on muscles for control and stability. It is worth noting that many strains originating from the wrist will also project result in pain towards the elbow, this is due to the fact that many of these muscles stabilising the wrist have attachments near the elbow joint. “Golfer’s elbow” and “tennis elbow” are examples of this.

Illustration of overextension in the elbow while delivering force

Apart from the dull prospect of rest and analgesics when strain injuries occur, an important component here is to train your body control in order to prevent hyper-extension or over-rotation. Boxing classes are good for this, as they tend to lay a lot of focus on controlling your blows, and the motions are very much the same as the ones used in HEMA. And again, buff up!

The wrists are yet another joint where women tend to have a larger range of motion, and where the difference in strength can play an important role when it comes to injury tendencies. It is also here, and in the fingers, that the raw force of a blow is projected, which places enormous demands on the muscles, and the ligaments, of the wrist. Here it is primarily flexors and extensors of the wrist that come into play, but also muscles involved with the aforementioned rotation of the lower arm. In this area it is really all about muscular resistance training to increase your strength, as this is what will give you the ability to better handle the repetitive stress that you subject your hands to.

As for fingers… Skin abrasions and the likes are, as most of you say, a matter of gear and getting used to it. When it comes to finger breaks, again gear is helpful, but if you want to be safe, execute your techniques better and cover those hands!

I will briefly discuss the matter of the neck and back. As I mentioned before a lot of pain that is felt in the neck and upper back can be a symptom of problems elsewhere, but may also be attributed to actual problems in this region. When executing techniques properly you incorporate use of your entire body in delivering force, much of which is projected from your “central body” via the axial skeleton(6). This places huge demands on your back and core muscles, because these are responsible for maintaining a stable base from which your arms and legs can do their thing. Worth mentioning is that many of us lead typical modern lifestyles with relatively little everyday activity; and we spend a lot of time sitting down, often in less than optimal positions. In addition to this, we put different strains on the different halves of our body according to weapon type and “handedness”, which projects throughout the body. This gives us an uneven and often somewhat sub-par base to work from, which may result in multiple types of injuries and pain.

Illustration of posture with poor muscles strength and core incorporation in comparison to a more functional pose, side view

Illustration of posture with poor muscles strength and core incorporation in comparison to a more functional pose, note height difference, back view

My suggestion is that you do what is necessary, not only treating the pain with analgesics, rest, massage etc. but that you also start working to give yourself better core and back muscle strength and control. Muscular resistance training to build up back muscle, and particularly muscles of your “weak” side can help. Combine this with focused functional core training and you’ll give yourself a head start, not only when it comes to avoiding pain and injury, but also to delivering more powerful techniques.

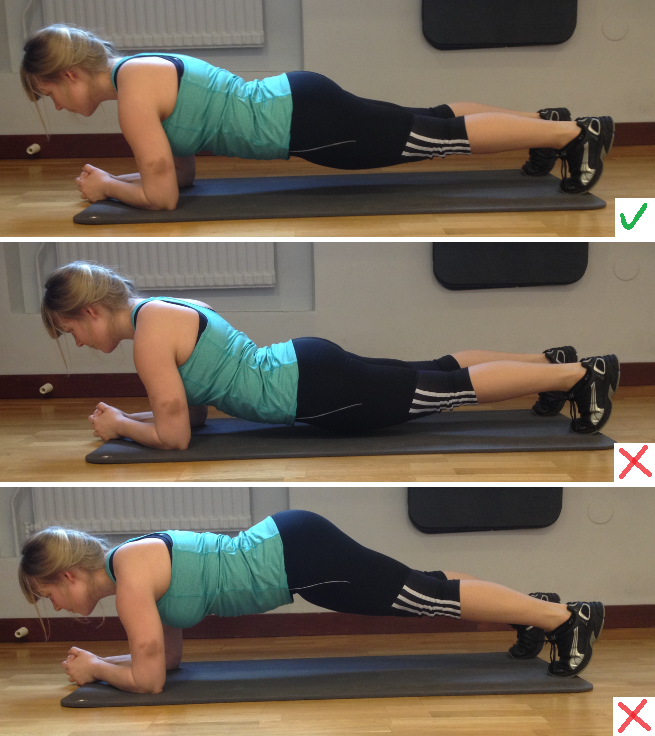

Illustration of performing a plank, and common mistakes made when core musculature is not incorporated fully in the exercise

Application of core training in a fencing oriented exercise, sitting on ball without floor contact while performing drills

The lower extremity is in its simplest form a blueprint for the upper extremity, with some “slight differences”, like knee caps for example. Few of you mentioned problems with your hips in forum discussions, although hips may give issues further down in the leg, or act as indicators for problems lower down.

Moving on to the knee, which many of you did mention. Much like the elbow it is a complex joint and a common site of injury in many sports. The knee consists of three bone components and a multitude of ligaments, tendons and other bits and pieces. The thigh bone (femur) of the upper leg joints connects to the shin-bone of the lower leg, but has no contact whatsoever with the calf bone. Last is the knee cap, or patella, which is highly important for optimizing force output from the muscles on the front of the leg. The patella is known as a sesamoid bone and is embedded in the ligament of the quadriceps muscles. The knee joint is fairly flat, but has a multitude of ligaments, collateral and cruciform, that work to stabilize it, this also means that there are multiple points for injury and strain. When flexing or extending the knee while pointing the foot in the direction of the knee, without rotating the foot sideways, the knee joint is fairly stable and can handle quite a lot of force: as all of the ligaments and tendons are when strained under optimal conditions. However, this is rarely the case in fencing where low stances and quick lunges are an integral part of the footwork. This means additional strain at “odd” angles where our ligaments are not optimized to work. The collateral ligaments act to protect the knee from “folding sideways” and the cruciform ligaments work to hinder the joint from gliding backwards-forwards in its own plane of motion. Our knee ligaments are particularly at risk when it comes to fencing footwork with a bent knee in a forward position, especially if the knee is in front of the foot, or if the knee deviates from a straight line between the foot and hip. Immediate treatment for when the damage to the ligaments is already done is again analgesics and lowered intensity level training. However, for recovery, practising control and “buffing up” is once again the recommended concept.

To strengthen ligaments takes time, but by building additional strength of the muscles surrounding your knee and practicing control you can lower the risk of re-injury as well as and potentially increase the efficacy of your footwork. By having stronger muscles you can provide greater stability and relieve some of the stress you put on the joint at the more difficult sub-optimal angles, and thus a lowered risk of injuring ligaments. Practicing control under pressure of weight or strain in controlled conditions will also better prepare you for handling them “live”.

Moving on to the ankles and feet, which were not the biggest groups of affected areas, seem less often affected by pain, but are none the less worth discussing. The feet are very much essential to how we perform, as they are what anchors us to the ground and allow us to propel ourselves forward. The simple act of walking puts a fairly large strain on the foot, a force of approximately 1000 N per foot per step (7). Factor in that we lunge at odd angles and with little time for calculation. A common problem associated with this type of footwork is over-stretching of the ligaments that surround the ankle joint, the ligaments that hold the two bones of the lower leg together, or the ligaments that maintain the arch of your foot. I will quickly discuss the latter of these groups. These ligaments in the sole of the foot are known as the plantar fascia and along with the structure of the bones in the feet help maintain a transverse and a longitudinal arch. This arch is very important, as it allows for shock absorption and facilitates the normal use of the muscles in the lower leg during simple tasks such as walking. If the arch is damaged or stretched, pain in the lower leg can result in something similar to MTSS (8). This can also be a problem for those who practice on very hard ground. In order to prevent these problems, you need to train the muscles and control of your feet. There are various methods, but they include things as simple as rolling a tennis ball around on the floor using your toes. Also, make sure your footwear is not overly worn, is of good quality and a good fit (9).

Over-stretching of the outer ligaments of the ankle while stretching the inner leg, not placing the sole of your foot on the ground reduces this issue.

Overstretching of the ankle while stretching the front of the leg, a grip around the ankle or below it removes this risk.

Most of us will have experienced sprains, and this is where I suggest some caution. Their seriousness is often underestimated. First of all, there is a type of “higher level” sprain whereby ligaments that hold the two bones of the lower leg can be stretched or torn. These are relatively unusual but tend to occur in combination with breaks. Moving on to the the big bad boy of the ankle sprains we have is the so-called “inversion sprain”, whereby the ligaments on the “outside” of the foot are stretched or ruptured, often after quick, not completely controlled, forward or sideways footwork in a forward or sideways motion. It is important not to take this type of injury too lightly, as it has an up to 60% recurrence, and tends to worsen at every new sprain (10). Initial elevation is essential to reduce swelling. In the long-term it is important to build up new control and strength in the ligaments, which even for simple sprains can take weeks or months to achieve. As for building back up to good footwork simple things like standing on one foot while brushing your teeth, or practising skipping rope can be very helpful (10). If you want to try and avoid it happening I recommend the same exercises to avoid such an injury in the first place, as well as sideways step ups and controlled foot work drills where focus is on your feet and not on the weapon.

Uneven weight distribution and deviation of the right leg while squatting, not uncommon for fencers. Problem reduced with additional awereness and correction of knee position and weight distribution

Over/hyper-extension of the knee while standing, places unnecessary strain on the ligaments, reduces balance and affects posture

Of course there is also the risk of stress-fractures in the bones of the feet and compression of nerves which will give rise to pain (11). You need to be attentive and seek a medical professional if the pain does not resolve quickly and has no obvious cause.

Ideally we would try to implement “preventative physiotherapy” within HEMA, where we build up good muscular strength and control to keep ourselves from getting injured in the first place. There are many things to be aware of when it comes to injuries, but most important of all is to pay attention to your own body. Remember: if you push yourself beyond repair, you won’t be there to hit your friends in the face.

(1) Physiology of sports and exercise. Chapter 19, Sex differences in sports and exercise. Kenney. Wilmore. Costill. Human Kinetics, by Courier Companies Inc USA, 2012.

(2) Acta Orthop Belg. 2013 Oct;79(5):541-6. The incidence of knee and anterior cruciate ligament injuries over one decade in the Belgian Soccer League. Quisquater L, Bollars P, Vanlommel L, Claes S, Corten K, Bellemans J.

(3) Human movement. Chapter 10: p.156-7. Everett, Kell. Churchill Livingstone, by Elsevier Ltd, China, 2010.

(4)The infraspinatus muscle, supraspinatus muscle, teres minor muscle and the subscapularis muscle make up the rotator cuff.

(5) In the arm known as supination and pronation, a rotation of the ulna and radius in relation to the humerus.

(6) The axial skeleton projects from you pelvis to the skull and a central component is the spinal column.

(7) Biomechanics of Running and Walking. Tongen & Wonderlich. Available as online paper fromhttp://www.mathaware.org/mam/2010/essays/TongenWunderlichRunWalk.pdf

(8) MTSS stands for Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome, and refers to a condition where you suffer diffuse pain in the region of the tibia in the lower leg, which has multiple causes.

(9) Physical Rehabilitation of the Injured Athlete, 4th edition. Chapter 26: p581. Andrews, Harrelson, Wilk. Saunders, by Elsevier Ltd, China, 2012.

(10) Physical Rehabilitation of the Injured Athlete, 4th edition. Chapter 20: p440-442. Andrews, Harrelson, Wilk. Saunders, by Elsevier Ltd, China, 2012.

(11) Physical Rehabilitation of the Injured Athlete, 4th edition. Chapter 20: p457-459. Andrews, Harrelson, Wilk. Saunders, by Elsevier Ltd, China, 2012.

Original Post: http://esfinges1.wix.com/e/apps/blog/sucking-it-up-%E2%80%93-pain-attitudes-and