Written by Claudia Krause |

You want drama?

How about having the world’s most powerful men meeting at your place, one of them face down, begging for forgiveness? How about being accused of sleeping with the pope or having murdered your husband? How about charging into the enemy’s camp on your horse, your father’s sword in hand?

Matilda of Canossa certainly had her share of excitement, although nearly 1000 years later few people may have heard of her. In German “a walk to Canossa” still is an old-fashioned expression for eating humble pie. The woman who was instrumental in this event is well worth remembering. She was celebrated and feared during her lifetime and for centuries to follow, as military leader and powerful ally to pope Gregory VII and his successors. So, how did she become so formidable in a time where “equal opportunities” were not policy anywhere in Europe?

Childhood and youth

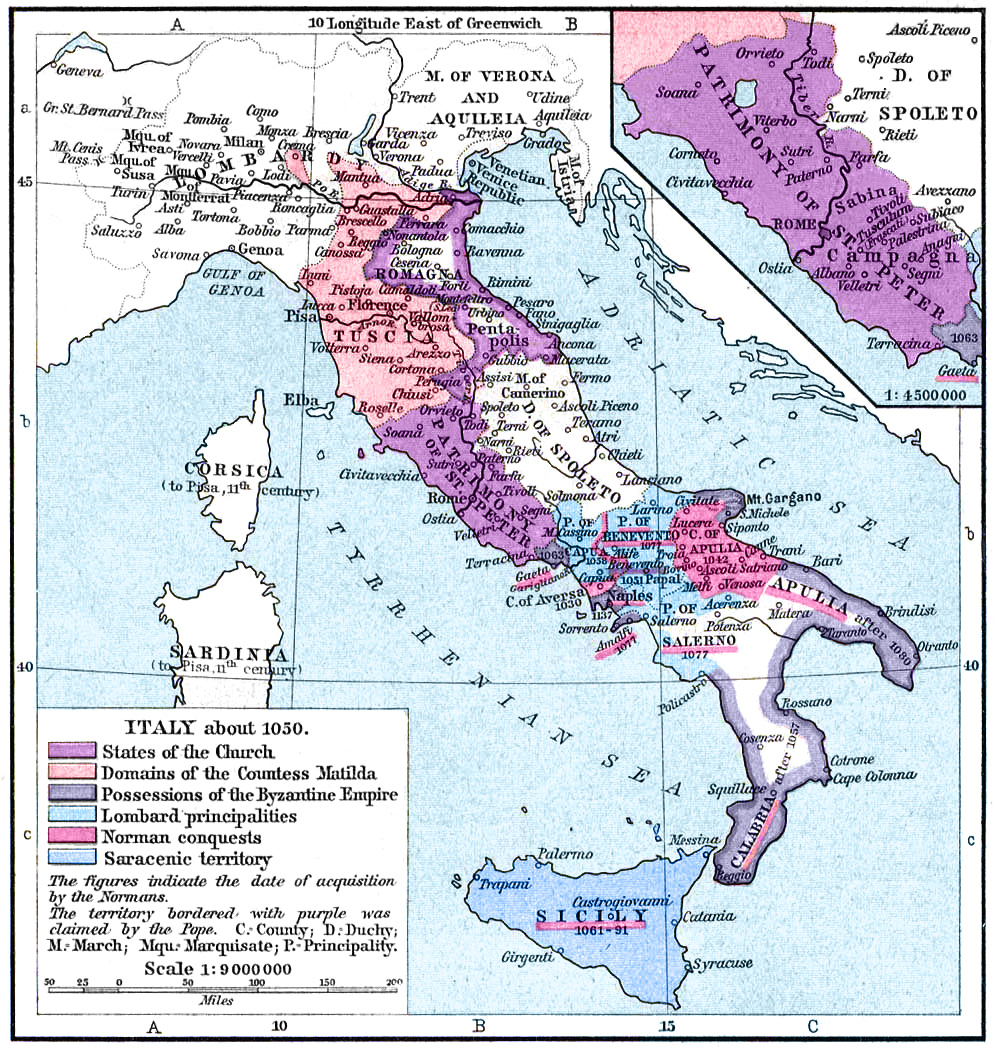

Things started rather pleasant and harmless. Matilda was born in 1046 as the third child into a noble Lombard family. For those of us who are historically challenged: the Lombards or Longobards were a Germanic people who ruled large parts of the Italian peninsula, before they got incorporated into the “Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation”. Lombard nobles continued to control Northern Italy, and had to negotiate alliances with opposing overlords along the line. Matilda’s family was closely allied to the emperor of the time, Henry III. When Matilda was 6, her father died and things got tricky for her mother. In order to preserve her family’s interest she remarried. The stepfather, however, was at odds with the emperor. Henry III didn’t take kindly to the alliance and abducted mother and daughter to Germany. By the time an agreement was reached, and they returned to Tuscany some years later, all her siblings had died. Matilda was acknowledged heir to the largest territory south of the Empire.

Matilda’s mother and stepfather were heavily involved in papal politics. Given that Matilda was going to inherit the “family business”, she might have taken an active part in the proceedings. Aged 21, she went on a military campaign with her stepfather, overseeing part of the troops. She apparently did rather well. She had been betrothed to her stepbrother, “Godfrey, the Hunchback” since childhood, and lived for a while with him in Lorraine. However things didn’t go well after her stepfather died, and she left her husband after the early death of her only child, never to return.

Reign in Tuscany

Matilda’s husband started siding with the emperor of the day, Henry V. She remained loyal to pope Gregory VII. Maybe this led to her estranged husband brandishing rumours about an affair between the two. Soon after he met his death, when he was ambushed “following a call of nature” while campaigning in Flanders. There is no evidence that Matilda was involved in his death, but it was timely. Soon after her mother died, and as a widow she had nobody to contest her heritage to Tuscany. By this time she was one of pope Gregory’s most trusted military advisors. It was on her suggestion that pope and emperor met at Canossa when the latter’s intentions weren’t quite clear. It was also with her help that a deal was brokered following the emperor’s rather effusive “apology”.

When years later tables were turned, and the pope was forced into exile, Matilda stood her ground, continued to control the Apennine passes and act as intermediary for papal messages and defeat Henry’s attempts to take Rome. When he once again confronted her in her own territory he suffered defeat at Canossa in 1092. Several cities in Northern Italy broke from the emperor’s rule, as did his eldest son and wife. Attempt at retaliation failed, and in 1095, Matilda managed to establish Gregory’s successor in Rome. Henry IV’s influence in Italy never recovered and he died a defeated man in 1106. His successor, Henry V, was luckier. When he “visited” Northern Italy, Matilda acceded him the rights to territories which had been disputed for 20 years. He crowned her “Imperial Vicar and Vice-Queen of Italy” in return. When she died 4 years later aged 69, from gout, a biography had already been written and dedicated to her. “Vitae Matildae” by the Benedictine monk Donizio, might be a tricky read, as it’s in Latin Hexameters. Translations in German and Italian are fortunately available.

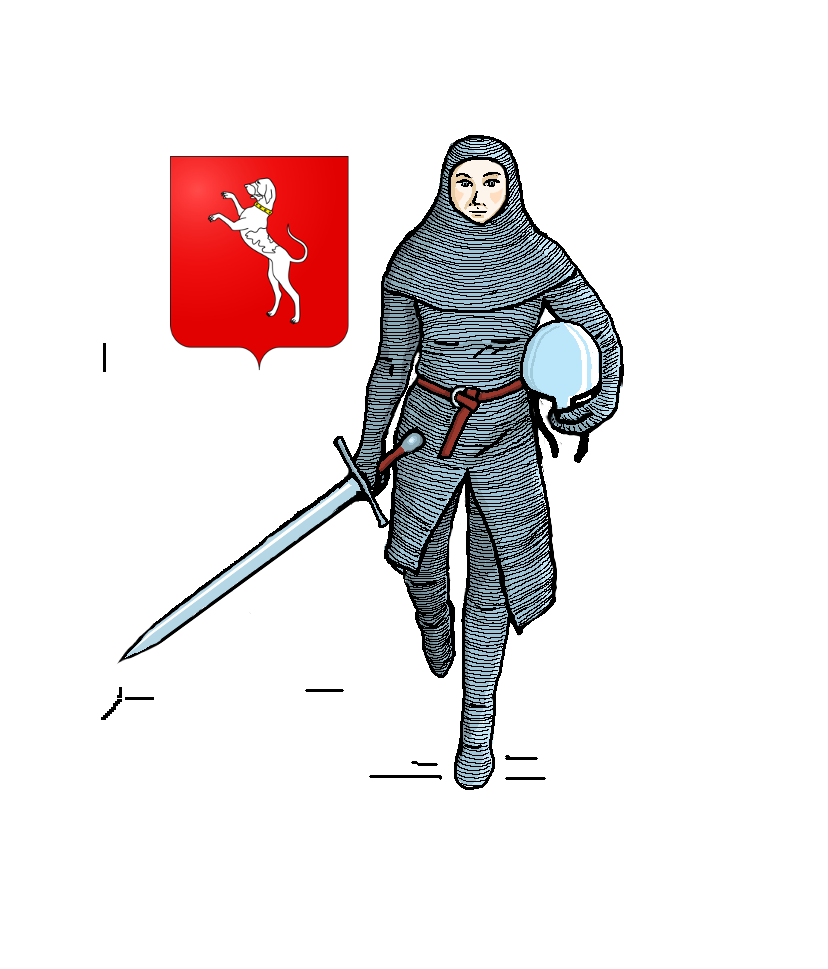

Drawing Matilda

As part of an Esfinges project we were invited to draw historical warrior women. Contemporary pictures were not much help drawing Matilda lifelike, given the rather schematic style of the period. Later portraits are as much subject of conjecture as my own. Descriptions of her appearance don’t seem to exist. Later sources state that she had been taught strategy, tactics, riding and wielding weapons in her childhood, but scholars can’t agree here. She has been documented to have been active in campaign, and reportedly rode out with her father’s sword. We now know that the weight of armour worn at the time would not have been a problem for a healthy woman to fight in, let alone wear. So I have pictured her on her way to her horse. Her shield is still on the wall. It features the jumping dog of the House of Canossa. She wears chainmail and nasal helmet customary for wealthy warriors of that time in Europe, and carries her father’s sword as per legend. Woe to those who cross her!

The views expressed herein are those of the author and not necessarily the views of Esfinges.

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Matilda_of_Tuscany

Newark, Tim. Women Warloards: An illustrated military history of female warriors, The Bath Press, London, 1989; print

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Godfrey_IV,_Duke_of_Lower_Lorraine

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Components_of_medieval_armour

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lombards

http://biography.yourdictionary.com/matilda-of-tuscany

http://www.uni-mannheim.de/mateo/desbillons/hola/gif/hola25.gif